The myth of drug traceability in India

India launched a drug traceability programme more than a decade ago with the objective of stemming the flow of counterfeit medicines to Africa. That effort failed and the mandate was withdrawn earlier this year. Avi Chaudhuri, PhD | Founder, The Kulinda Consortium explores the factors that led to that failure and the immense harm it caused to both India and Africa.

The year was 2011. All of a sudden, drug makers in India started talking about Track and Trace and how they all needed to have that in place in quick order. A throng of solution providers suddenly emerged to proclaim they could deliver just that to an eager clientele. Most of these merchants were machine makers, package line integrators, IT specialists or unaffiliated technology companies, all of who suddenly saw a golden opportunity to capitalise on an emerging craze. Despite their claims, these virgin entrants had no technical competency in deploying a full traceability programme, much less any appreciation for the massive data complexities and implementation challenges involved in such an operation.

But what led to this sudden obsession with Track and Trace across India? Around that time I was engaged in helping Indian pharmaceutical companies battle their domestic counterfeiting issues and therefore had a front row seat to what was unfolding. It all began when India’s Commerce Ministry launched a search for the best way to combat counterfeit medicines that began to appear across Africa with a “Made in India” label [1]. In the end, it was European standards organisation GS1 and its Indian affiliate that influenced the Ministry to mandate a Track and Trace programme to all drug exporters [2].

Fast forward to 2025 and it is now clear that India’s decade-plus effort to implement a drug traceability programme has had a fatal outcome. The experiment faced multiple obstacles that in turn led to persistent delays and shifting deadlines. In the end there was only one predictable outcome. The Commerce Ministry was forced to withdraw its traceability mandate earlier this year [3].

Here, I explain why India’s drug traceability programme was always destined to fail and how vested financial interests were responsible for that failure.

A) What does a drug traceability framework look like in the Indian context?

A rather remarkable phenomenon unique to India is the staggering number of companies that claim to provide an end-to-end Track and Trace programme. Many among this group are responsible for India’s drug traceability failure due to a troubling ignorance of the field. It is therefore important to review what is involved in deploying a full end-to-end Track & Trace programme so as to understand why they did not grasp the enormity of the challenge they signed up for.

Product tracking in many cases is actually a straightforward process. Courier companies, for example, routinely track individual packages and letters with node-to-node data capture perfection on the transport progress. Although there is a high demand for data processing, the fundamentals behind that practice are uncomplicated. Supply chain tracking of medicines, on the other hand, must confront the challenge of huge volumes combined with the need to have many identical products be transported and handled by multiple independent participants. Enter inferential tracking.

The first step in that process involves placing a unique serial number on every package by way of a

machine-readable symbol such as a 2D barcode. Although conceptually simple, the process of serialisation is fraught with technical challenges in ensuring a properly readable barcode is printed.

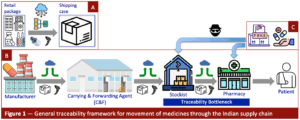

The next step at the production line is to register the accretion of multiple drug packages into larger ones, such as a shipping case. This process, known as aggregation, requires digital integration of nested package structures to create an electronic tree of linked serial numbers, which is then uploaded to a central portal (Figure 1A). Tracking the uppermost package, such as a shipping case, can then inform all stakeholders of the exact location and custodian of each of the constituent drug packages.

The third step in the traceability regime unfolds after completion of serialisation and aggregation.

Shipping cases are sent through a series of supply chain nodes starting at the manufacturing site (Figure 1B). In India, the first waypoint is usually a large warehousing facility operated by so-called Clearing and Forwarding (C&F) agents. From there, drug shipments are sent out to a vast network of regional distributors (wholesalers) referred to as stockists and then ultimately to local pharmacies. At each nodal point, incoming and outgoing shipments must be scanned and uploaded, thus creating a full electronic trace across the entire supply chain from plant to pharmacy.

The weakest link in the above scenario takes place in the transfer of medicines from the stockist to the pharmacy. I call this the Traceability Bottleneck (see Figure 1B). And this is where we find the greatest vulnerability and why India’s Track and Trace programme could never have succeeded, as explained next.

B) Why was a drug traceability programme inevitably destined to fail in India?

A commonly held attribution for the Commerce Ministry’s withdrawal of India’s drug traceability programme is that many drug makers struggled to implement the aggregation step that in turn caused multiple delays and deadline extensions [5]. In the end, it just became untenable to continue down this path. But even if the package aggregation step could have succeeded, it still would not have helped to rescue the programme because it would then have blown up due to the Traceability Bottleneck at the stockist–to–pharmacy transition point.

As discussed above, an essential part of the preparatory work for tracking is to accumulate retail

packages into shipping cases and create an aggregated digital relationship. The most common practice among drug makers is to place a single brand and dose level, referred to as the stock-keeping unit (SKU), into the shipping case. In other words, these are homogeneous cases containing a single SKU and almost never mixed in with other SKUs or drug formulations. The integrity of the shipping cases is maintained through the C&F node and then transferred as such to the stockists. And this is where things break down.

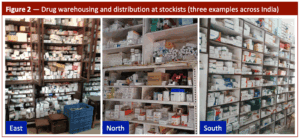

Stockists in India never send retail drug packages to pharmacies by way of the original shipping case because few of them rarely require such high-volume delivery of a single medicine. Instead, pharmacies will generally place orders with their supplying stockists for different drugs at much smaller quantities of each, sometimes even down to just a single strip. This has two consequential impacts on the traceability programme. The first is that stockists must open the shipping cases delivered to them, remove all drug packages and store them at their premises — in effect creating their own small warehouse of stocked retail packages (Figure 2). The stockist can then pick and pack different retail items for delivery to their pharmacy clients based on the drug orders received.

It is the second consequence that is however the most impactful — the entire process of inferential

tracking has just become disrupted at the stockist level. All the effort and expense that went into creating the aggregated digital tree by the drug maker, as shown in Figure 1A, has now devolved into a disparate collection of many different SKUs placed across the stockist’s shelves, tables and even its floor. The disciplined process that produced both physical and digital integrity in the supply chain up to this point now becomes a dispersed heterogeny across a vast network of independent business operators.

A complete traceability programme must however still contend with the next step as shown in Figure 1B — i.e., track the medicine from the stockist to the pharmacy. Stockists will generally compile various different drugs and place them into a box for delivery. If the tracking process were to continue through this next shipment, then the serial numbers on all those assorted retail packages must now be re-captured and entered into the tracking programme. In other words, the stockist must now undertake a re-aggregation exercise, often referred to as re-work, on the heterogeneous delivery package. And then those packages would have to be scanned after arrival at every pharmacy to complete the track. This would then complete the requirement for a true end-to-end drug traceability programme.

It is estimated there are over 65,000 stockists in India [5]. The very aggregation step that could not be fully executed across the much-smaller and disciplined drug manufacturing landscape would now have to be repeated at each and every one of those stockists, with drug arrival then to be captured at over 550,000 pharmacies across the country [6]. That is the Traceability Bottleneck in the programme. The idea that an end-to-end Track and Trace programme can be executed across this vast and unruly bazaar is nothing short of a fantasy. And that leads us to the following blistering conclusion — an Indian drug traceability programme could never really have been executed in the first place, and very likely never will.

C) Why is it futile to create an anti-counterfeiting programme based on traceability?

Recall that the driving force behind India’s effort to install a drug traceability programme in the first place was to eliminate the presence of fake variants. That idea however faced two serious setbacks from the outset in light of the above discussion.

Counterfeiters have evolved their craft from the early days as a cottage industry to a modern and

sophisticated operation. Notwithstanding the cunning extent of their perfection in replicating genuine drug packages, counterfeiters must still find a way to deliver their fake products through the supply chain and into the hands of consumers. We return to Figure 1 to see there are two main points for that act to take place — the stockist and the pharmacy (Figure 1C).

There have been recent reports of stockists from across India being caught for distributing fake drugs [7-9]. However, it remains unclear until the judicial process plays out whether they were willing participants in a criminal act or instead duped into participation in the belief they were receivers of genuine medicines. The first possibility is a damning indictment of why a traceability programme will not stop entry of counterfeit drugs into the marketplace. Even if a relatively small subset of stockists choose to participate in the crime, then no traceability programme regardless of its functional excellence will stop counterfeiters from establishing a clandestine network to grow their lucrative business across India [10].

But what if we take a more charitable view that a corrupt stockist will decide against distributing fake drugs because of the strong digital oversight that comes with traceability, or that the honest ones would be protected from being victimised by unscrupulous traders. And therein lies the second paradox — the mere prospect that stockists and pharmacists could be either deterred or protected by a Track and Trace programme was always a fallacy because it just could never be implemented.

D) How did the idea of drug traceability take hold in India in the first place?

The foregoing discussion dashes any hope that a drug traceability programme can solve the very serious problem of counterfeit medicines at home and abroad. In the next section I take up who is responsible for creating and promoting that grand delusion. To set the stage for that discussion, it is necessary to first map out the key players in the traceability ecosystem and the business factors that drove their mission.

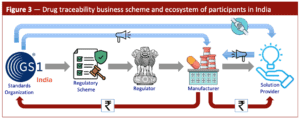

The discussion that follows is based on the schematic figure below (Figure 3).

Government regulators often canvas and then select a solution they believe is best suited for the

problem at hand. Such was the case circa 2011 when the Commerce Ministry sought ideas to arrest the sudden rise of counterfeit drugs across Africa that were discovered to mimic Indian brands. It was the Ministry’s duty to come to the protection of India’s domestic drug industry by finding a solution. GS1 and its Indian affiliate had an outsized influence in that selection process because of its entwined connection with the Commerce Ministry [11]. The key outcomes that unfolded from that relationship are shown in Figure 3 by way of the gray arrows.

GS1 had promoted the theory that drug traceability is ideally suited to combat counterfeiting [12,13], and therefore not surprisingly the regulatory scheme it advocated was based around that objective. The Commerce Ministry not only adopted and imposed that view upon the drug makers but then went one step further to ensure that they had to specifically follow GS1’s coding formats [14]. GS1’s success was not just restricted to India. The same tactical approach led to adoption of drug traceability in other emerging countries that are struggling with their own counterfeiting problem [15,16].

Indian drug makers were not in a position however to suddenly implement a Track and Trace programme and therefore needed the help of a solution provider to deploy all three required components — serialisation, aggregation and tracking. And this is when a bevy of them suddenly came out of nowhere to announce their capabilities, even though most had no prior experience in doing so.

It would have been expected that the role of a standards organisation would end with regulatory

adoption. That was not the case however. GS1 India launched an active campaign of programme fulfillment through strategic engagements it formed with various solution providers [17] and their trade organisation [18]. The blue arrows in Figure 3 illustrate the outcome of that bond, which included a sustained marketing operation aimed at the pharmaceutical industry [19,20]. The goal seemingly was to ensure that GS1 standards were strictly followed, including use of its proprietary barcodes that could only be purchased through their portal [21]. GS1 India and the solution providers were rewarded with substantial earnings from drug makers who had no choice but to comply (red arrows in Figure 3).

E) Who is responsible for perpetuating the delusion of drug traceability in India?

President John F. Kennedy famously said, success has a thousand fathers but failure is an orphan. In the case of India’s drug traceability failure, there are actually three orphans.

We start with the third orphan — India’s pharmaceutical industry and its various trade bodies. Although they were not involved in either proposing or promoting a drug-tracking programme, they were complicit in its failure through passive acceptance. If anyone knew about the complexities of their own supply chain and the inevitable bottleneck at the stockist-to-pharmacy transition point then it was surely the drug makers themselves. The Indian Drug Manufacturers Association (IDMA) did file an unsuccessful lawsuit to halt the traceability programme. However, that suit was based only on the onerous cost faced by its members to comply with the regulatory order. There is nothing in the public record to suggest that a coherent argument was made by the drug industry that a traceability programme will not succeed in eradicating counterfeit drugs, even though they owned powerful operational arguments and were in the best position to persuade the regulators. That incalculable misstep by drug makers led to substantial manufacturing disruption and a cost to them in crores of rupees spanning a decade.

The second delegation to the orphanage is clear from the previous discussion and therefore can be

dispensed with quickly. The sudden entry of newcomers who projected themselves as experienced Track and Trace solution providers was nothing short of a scam. Most simply did not have the qualifications to deploy such a complex programme. The result was a ramshackle approach to implementing serialisation in the early days. Then came the sobering realisation of the challenges associated with the critical aggregation step, producing sustained delays that eventually led to regulatory withdrawal of the entire drug traceability programme.

The top spot for attributing failure is reserved for the chief architect and promoter of India’s drug

traceability experiment. As the global leader in developing coding and traceability standards, GS1 and its various country affiliates are staffed with technical experts who possess substantial knowledge of supply chain operations. Consequently, it is inconceivable that they were not aware of the substantial challenges in not only implementing serialisation and aggregation at Indian production lines but also the inevitable Traceability Bottleneck that would emerge down the supply chain.

GS1 also had to be aware that the Indian government would have no authority to compel foreign

distributors to undertake the needed re-aggregation exercise at its facilities. And yet it consistently

promoted drug traceability with the certain foreknowledge that such a programme would have serious

operational challenges that would cause an eventual crash, whether in India or abroad.

F) What was the driving force in the selection of traceability and what harm did that cause?

We are left with the indisputable conclusion that a Track and Trace programme was not fit for purpose in India for eradicating counterfeit drugs. And given the above arguments, it would be an immense stretch to accept that GS1 was not aware of that fundamental fact. So why then does a standards organisation go out of its way to invest heavily in ensuring that the drug industry adopt traceability and then only so through its proprietary coding formats?

The answer comes from the business side of traceability. GS1 is responsible for creating standards whose adoption then earns it revenue from drug companies that are forced to comply with those very standards. There is a fundamental conflict of interest at play here because the financial benefit that GS1 accrues is a direct outcome of its government engagement [22]. The influence exerted on government officials for what it must have known was not in the best interests of the country ended up causing great harm to India [23].

The harm was however not restricted just to India. GS1’s advocacy that a drug traceability programme would solve the counterfeiting problem in Africa led the Indian government to abandon far more effective solutions that were readily available back in 2011. As a result, African nations continued to suffer from the epidemic of counterfeit drugs, which only continued to grow over the past decade to become a public health crisis that according to the United Nations now kills more than half a million people annually [24,25].

During that period, India remained helpless in the face of continued penetration of fake medicines

mimicking its domestic brands. And given its role as the largest supplier of medicines to sub-Saharan Africa [26], India was uniquely positioned to greatly reduce suffering and save lives there over the past decade. And that is the tragedy of it all — the devastating consequence on African humanity from India’s decision to pursue a programme that never had any chance of success.

G) Moving forward

The objective of this article was to offer a reflective analysis of why a decade-plus effort to install a drug traceability programme in India did not succeed. There are three undeniable conclusions and associated recommendations that can now be advanced with sufficient confidence.

▪ The notion that a drug traceability programme could be implemented in India, and by extension in

other developing countries was always a fallacy. That conclusion is no longer up for debate. Moving forward, any thought of installing such a programme must be abandoned, and even the term Track and Trace should be dropped entirely from the lexicon of the Indian drug industry. Furthermore, continued printing of 2D barcodes on export drug packages is futile and should be abandoned because of their non-functionality in view of India’s withdrawn traceability programme.

▪ The claim that a Track and Trace programme can be used to eradicate counterfeit drugs is now shown to be demonstrably false. India tried that approach for a decade and has nothing to show for the massive disruption and expense incurred by its pharmaceutical industry. Moving forward, any suggestion that drug traceability can stop counterfeiting must be unequivocally rejected.

▪ The proposition that GS1 holds only the best interests of a country in solving its counterfeiting

problem should be repudiated. Had the Indian traceability experiment succeeded, it may have been possible to overlook its unarguable conflict of interest. Moving forward, regulators must refrain from acting on advocacy from GS1 on any programme related to counterfeiting. Otherwise, the certainty of yet another attributable failure would earn it the rightful scorn of a nation.

The idea that India could install a Track and Trace programme was always a myth. The one positive outcome from its failure is that it now serves as a potent warning to other developing nations who are considering a similar effort.

We are still left however with the urgent need to solve the serious problem of counterfeit drugs. India has begun a new journey to protect its citizens using a bold authentication approach. Although that programme experienced early problems due to the way it was designed [27] and then deployed [28], the effort is still in its infancy and consequently there is abundant opportunity for course correction. I have recently provided a blueprint for that correction based on my two decades of experience on the front lines of fighting counterfeit drugs, and which I believe would allow India to firmly establish an effective, enduring and economical programme to protect its citizens [29].

What happens next with the new authentication programme will determine whether India can serve as a shining example to the world on how to protect its people against the criminal elements that perpetrate the atrocious crime of counterfeiting medicines. I remain bullish that India will eventually succeed.

H) References

[1] https://www.cmaj.ca/content/181/10/E237

[2] https://content.dgft.gov.in/Website/pn5910.pdf

[3] https://pib.gov.in/PressReleseDetailm.aspx?PRID=2098042®=3&lang=1

[4] https://www.securingindustry.com/pharmaceuticals/india-extends-aggregation-deadline-for-drug-exports-until-april/s40/a10396/

[5] https://perpetuity.co.in/blog/f/pharma-distribution-–-an-emerging-theme-in-the-listed-

healthcare#:~:text=There%20are%20over%2065%2C000%20pharma,makes%20it%20ripe%20for%20consolidation

[6] https://www.numeralifesciences.com/Pharma-Distributors-in-India#:~:text=According%20to%20several%20reports%2C%20there,trustworthy%20Pharma%20Distributors%20in%20India

[7] https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/delhi/counterfeit-medicines-worth-over-rs-2-5-lakh-seized-from-delhi-wholesaler-9944475/

[8] https://www.securingindustry.com/pharmaceuticals/gujarat-hit-by-wave-of-falsified-qr-codes-on-medicines/s40/a16946/

[9] https://dca.telangana.gov.in/openfile.php?f=369

[10] https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/delhi/fake-life-saving-drugs-under-labels-of-top-brands-pan-india-racket-busted-6-arrested-10174397/

[11] https://www.gs1india.org/who-we-are

[12] https://www.gs1india.org/blog/why-is-traceability-important-for-consumer-safety/

[13] https://www.gs1india.org/blog/pharmaceutical-industry-supply-chain-risk

[14] https://content.dgft.gov.in/Website/pn5216_1.pdf

[15] https://app.box.com/s/qrdz2j8cst5xpuj8b2hf56qlvmg4wb9i

[16] https://app.box.com/s/2tj7p0ssqcpz35tfpnntf9u3l754esbe

[17] https://www.gs1india.org/find-a-solution-provider

[18] https://www.labelsandlabeling.com/news/associations-and-events/aspa-gs1-india-sign-mou

[19] https://www.expresspharma.in/gs1-india-hosts-healthcare-conference-on-navigating-the-future-of-healthcare/

[20] https://gs1indiacontent.blogspot.com/2020/04/gs1-traceability-service-enables.html

[21] https://www.gs1india.org/register-for-barcodes

[22] https://www.gs1india.org/how-we-engage-with-the-government/

[23] https://www.expresspharma.in/a-defining-opportunity-for-clarity-from-gs1/

[24] https://news.un.org/en/story/2023/02/1133062

[25] https://www.theguardian.com/world/article/2024/aug/04/fifth-of-medicines-africa-substandard-fake-research

[26] https://www.thebureauinvestigates.com/stories/2025-04-16/indias-drugs-industry-global-medicine-market

[27] https://www.securingindustry.com/pharmaceuticals/india-s-drug-qr-coding-programme-anatomy-of-a-debacle/s40/a16877/

[28] https://www.securingindustry.com/pharmaceuticals/india-s-qr-code-programme-part-2-rating-the-drug-makers/s40/a16919/

[29] https://www.securingindustry.com/pharmaceuticals/india-s-qr-code-programme-part-3-how-to-repair-and-reform/s40/a17040/